Importers in several Middle Eastern and North African (Mena) countries have struggled to fulfil their grain purchase contracts owing to an ongoing shortage of foreign currency, with an increasing call for international monetary institutions to step in to handle the gap, preventing any significant fallout from large volumes of unloaded grain.

Dollar and euro shortages in major importing countries such as Egypt, Pakistan, Iraq, Bangladesh and Morocco have, in recent months, resulted in ships being stuck at port and grains delivered to silos but inaccessible to the original, or prospective, buyers because they have been unable to source foreign currencies to pay sellers. The issue has been an intermittent problem for some years, according to market participants, but this recent cycle has been particularly severe, and only expected to worsen — thereby negating the effects of softening grain prices.

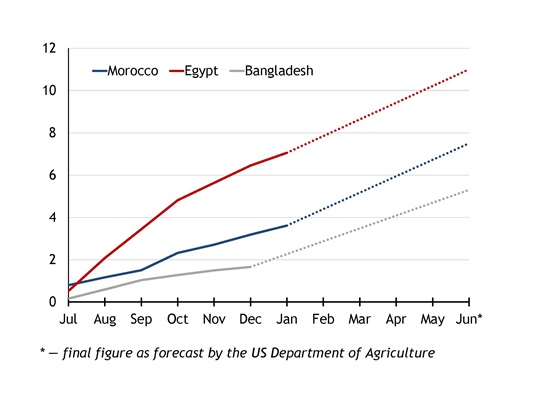

2022-23 wheat imports (mn t)

Egypt’s government had been considering a barter system of exchanging gold for grain, but may have decided against it because of the risk to further – and uncontrolled – devaluation of the Egyptian pound, according to market participants.

A more likely solution in Egypt’s case – among others – could be financing by organisations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Islamic Trade Finance Corporation. This is expected by importers in the struggling countries as a foregone conclusion, no matter what conditions financing organisations may require in exchange, including containing inflation, restricting public debt and reforming the tax code.

But there is little agreement among participants, with some expressing doubt over whether the IMF would be willing to step in.

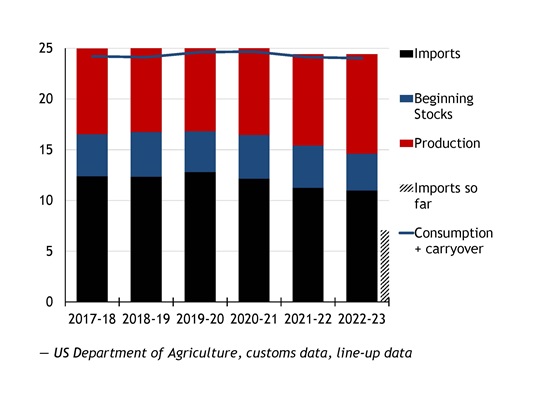

Egypt wheat balance (mn t)

The lack of trust in some buyers’ ability to fulfil obligations has even resulted in some multinational trading houses stepping away from Egypt — the largest wheat importer in the world — to refocus on other countries in the region such as Algeria, Oman and Kuwait.

That said, countries where the government secures financing for grain imports have been better at managing the situation by entering into direct negotiations with trading houses and in government-to-government talks – including with Russia. And barter schemes – in Egypt’s case, exchanging grain for fertiliser – remain a viable and achievable option.

In contrast, private importers without government backing in countries such as Morocco may find it more difficult to handle the issue, which has resulted in a focus on prompt purchases, as buyers only enter the market when they can no longer hold off.

Stuck volumes of grains were understood to be a relatively common occurrence in the region in recent months, with some market participants able to step in and secure cargoes at a discount after the original buyer had been unable to fulfil the contract. But this option may be less viable for volumes already unloaded and currently stored in silos in countries where buyers are unable to pay, and moving stocks out of silos would increase the costs beyond any potential for profitability.

Author Anna Sneidermane | Market Reporter - Agriculture

This article includes data and insight from Argus’ Agriculture Service.

Learn more about the Argus Agriculture package, including market intelligence, forward-looking analysis and proprietary supply/demand forecasts for the grain