A decade after the deadly Deepwater Horizon drilling rig accident cast a shadow over the US Gulf of Mexico's economy and ecology, offshore oil production in the region is hitting record highs and may be better positioned to weather the current downturn than onshore shale operations.

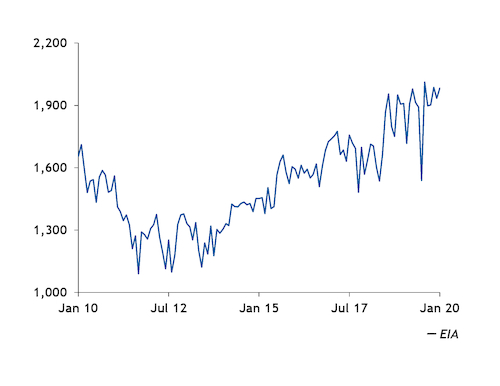

Offshore US Gulf production has risen steadily since 2013, averaging annual growth of about 100,000 b/d. Last year saw a 150,000 b/d boost, driven in part by the startup of Shell's deepwater Appomattox project, with total Gulf production hitting a record 2mn b/d in August. And since 2015, project development costs have fallen by about 60pc and operating costs by 7pc, according to consultancy Rystad Energy, thanks to adept use of technology improvements and existing infrastructure.

Updated industry practices and regulations implemented since 2010 were aimed at improving offshore drilling and production safety, but questions remain. The administration of US President Donald Trump has curtailed some regulations enacted after the 20 April, 2010, rig explosion at BP's Macondo well that killed 11 and spilled some 3.2mn bl of crude into the water 40 miles (64km) off of the coast of Louisiana. Further moves into deeper water, and its higher-pressure reservoirs, mean risks remain elevated.

US Gulf production will no doubt be hit by the current crude price collapse — the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) trimmed a prior forecast of 2021 production from 2.2mn b/d to about 1.9mn b/d, little changed from the expected 2020 level. But with the offshore dominated by oil majors and a few well-hedged independents, the massive Gulf of Mexico projects may be more likely to remain running in a downturn.

A dark shadow on the Gulf

As crude started spilling from Macondo 10 years ago this week, a sense of dread settled over the offshore energy industry. It would go on to become the largest ecological disaster in US history, damaging business interests across the region and giving a black eye to the whole industry – not just operator BP or drilling contractor Transocean. After a moratorium on new drilling enacted during the spill was lifted, offshore Gulf production was largely stagnant and remained mostly below the 1.5mn b/d mark for the next five years.

As onshore shale operators became more adept at transferring their expertise extracting natural gas to crude production, onshore oil shale became a greater focus for producers and investors.

But offshore projects — which tend to be significantly larger and more expensive than onshore fields, with lead times many years longer – continued to grind forward during the shale boom. Extensive infrastructure in the Gulf — including a several large production hubs built within the last 10-15 years and a vast network of subsea pipelines, has helped bring down average project costs. The growing use of lower-cost development options, such as subsea production equipment to tie new oil wells into existing platforms, has made expansions even easier.

Shell's Powernap project is an example of one such project, where a 35,000 b/d of oil equivalent (boe/d) deepwater field discovered in 2014 will be tied back to the existing Olympus production hub. Powernap is slated to come on stream at the end of 2021 with a breakeven price of less than $35/bl.

Chevron's $5.7bn Anchor project, the first field with an ultra-high reservoir pressure of 20,000 psi to undergo development anywhere in the world, is another sign of the strong economics for offshore projects. Chevron greenlighted the project in December and continues to work on reducing initial development costs to $16-$20/bl, from about $20/bl.

Still a risky business

A decade after the disaster, it is difficult to judge if a repeat of the Deepwater Horizon accident could occur.

The industry says it has reformed a safety culture that investigators found contributed to the well blowout, while it invests in technologies that improve safety and reduce blowout risks.

But a spate of offshore safety regulations put on the books after the accident have now been pared back under the Trump administration. The "well control rule" that bolstered safety equipment standards was weakened last year to save industry an estimated $152mn/yr, largely by cutting the frequency of testing of blowout preventers. Another rollback saved industry $13mn/yr by cutting safety standards for oil and gas production systems.

Environmentalists worry a culture focused around increasing production has become dominant. The Trump administration's top offshore safety official, Scott Angelle, was a lead opponent to the drilling moratorium after the 2010 blowout. Angelle earlier this year at an industry event said he sees it as his job to "grow the pie" of offshore royalties by supporting increased production.

Some price resilience

The current crude price drop and growing crude storage glut will hurt producers of all stripes, but offshore output may prove to have some resilience. Years of consolidation and tough operating conditions have narrowed the field offshore to major players such as Shell and Chevron with healthy balance sheets and a small number of well-hedged independent producers.

And while offshore wells have higher upfront development costs, their annual decline rates are much smaller — 10-15pc — compared with onshore shale wells that can lose as much as half their production volumes in the first year. This means offshore wells can generate steady cash flow with low operating expenses.