With expectations of a quick breakthrough in talks between Iran and the US to revive the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal now all but dashed, the leadership in Tehran appears to be preparing itself for the possibility of a protracted affair. And contrary to the narrative emanating from outside the country, Iran and its sanctions-hit economy are likely to be able to hold out for considerably longer than most would think.

Although US president Joe Biden has said he wants to rejoin the JCPOA, to date there has been little, if any, real shift away from his predecessor Donald Trump's maximum-pressure policy. Iran, which is still battling the deadliest outbreak of Covid-19 in the Mideast Gulf, remains under some of the most crippling US sanctions imposed. And with both sides firmly sticking to their positions, namely that the other must move first, the two remain at an impasse.

Tehran argues that the US should lift sanctions before Iran scales back its nuclear activities, as it was Washington that walked away from the deal in 2018. The Biden adminstration insists that it will not grant any sanctions relief to the Iranians until they are back in full compliance with the JCPOA.

Predictably, this has caused great frustration in Tehran, both in the streets and in the halls of power. The administration of President Hassan Rohani has since the November 2020 US election been pressing the Biden camp to move quickly to right his predecessor's wrongs. That initial urgency reflected, for the most part, the fact that Rohani's second and final term in office ends in August, but the sentiment was echoed even by Iran's supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

With little to show for their efforts, Iran's leadership appears to have changed tack. "We believe that opportunities must be taken advantage of, but we are in no hurry because, in some cases, the risks outweigh the benefits," Khamenei says. "We acted hastily on the JCPOA. But we are patient. If they accept our policy, everything will be fine. If not, the situation will continue. And we are fine with that."

Given the clear damage that the sanctions have inflicted on the Iranian economy to date, one could be forgiven for thinking this is just bluster. Iran has clearly gone through a very tough time since 2018, and Iranians, without a doubt, overwhelmingly want sanctions relief. But should it not come in the next three, six, nine or even 12 months, will the economy crumble? Almost definitely not.

Trump this

In the early months of the Trump administration's maximum-pressure campaign on Iran in 2018, many analysts were predicting the worst. Some of them felt Iran would go the way of North Korea and completely isolate itself, while others expected it to follow Venezuela into collapse. The economy of the once-thriving Latin American Opec producer is in tatters, driving more than 5mn Venezuelans to emigrate in recent years, while its oil production has fallen to multi-decade lows of below 500,000 b/d.

But, despite suffering what Trump labelled "the toughest ever sanctions", the Iranian economy has fared far better than many expected. That is primarily down to its make-up and diversity, and more specifically, a popular misconception, says Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, founder and CEO of Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, a think-tank focusing on Iran's economy.

"The miscalculation in expectations stems from the fact that Iran is perceived as an oil-based economy. So, when the sanctions did have a serious detrimental impact on the oil sector, and people look at those indicators, they assume that spells disaster for the economy at large," Batmanghelidj says. "But the oil sector generally accounts for 15-20pc of GDP. And the percentage has remained consistently low for the last 20 years."

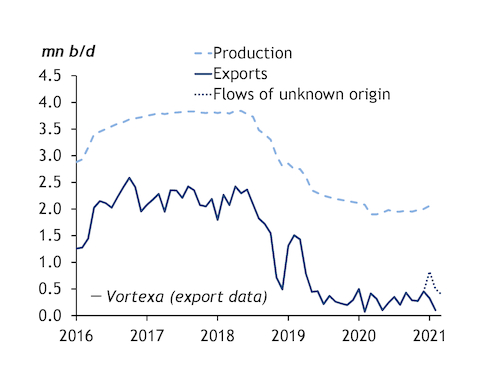

For the Iranian year that ended in March 2020, the latest for which official data from the Central Bank of Iran exists, the contribution of the oil and gas sector to the economy was just 7.4pc. This reflects the full impact of Trump's campaign which, at its height, forced more than 2mn b/d of Iran's oil exports off the market, contributing to a precipitous fall in the country's crude output to below 2mn b/d — the lowest since the start of the Iran-Iraq war in the early 1980s.

But Iran's oil exports and production have recovered incrementally since the start of 2021, supported by increased direct and indirect purchases of its crude by long-time customer China. Argus assessed Iran's output at 2.06mn b/d in February.

Trade strategy

When Iran's oil and gas sectors are hit, others — be it agriculture, services or manufacturing — come in and fill the gap, Batmanghelidj says. And with that diversity, Iran has been able to further cushion itself against such external pressure by deploying a trade strategy that combines import substitution and export promotion, says Bijan Khajehpour, managing partner at Vienna-based consultancy Eurasian Nexus Partners.

"The traditional policy reaction to this kind of extreme pressure is to just switch and go for import substitution. Say we will not import anything, and just produce everything ourselves," Khajehpour says. "Iran does partly engage in import substitution, but at the same time export promotion."

Export promotion involves the targeting of sectors where Iranian products can compete in international markets, at least on a regional level, particularly at a time when Iran has suffered a market devaluation of its currency, making its goods even more competitive. "Iran does not want to isolate itself. It wants to remain engaged," Khajehpour says.

Tomorrow never comes

Although Iran has been under some form of sanctions for much of the past 40 years, the last three years of Trump's maximum-pressure policy have arguably been the most difficult to navigate — because of not only the severity of the sanctions, but also Iran's reduced circumstances relative to previous years as a result of lower global oil prices.

Prior to the last round of sanctions in 2012, Iran enjoyed several years of $80/bl-plus oil prices that helped build reserves in its sovereign wealth fund, the National Development Fund. The Rohani administration, however, only got to sell at an average price of $50-55/bl in the period between the lifting of sanctions in January 2016 and their reimposition in May 2018.

Iran today has around $88bn in foreign exchange reserves, although only 8-9pc of that is accessible in the country, according to the IMF, with the remainder tied up in escrow accounts in countries that bought Iranian oil prior to the return of the sanctions. Yet after nearly three years of negative year-on-year GDP growth, Iran returned to growth in the second half of 2020, and is expected by the IMF to grow by 3.2pc this year and by 1.5pc/yr in the following two.

Although this is not enough to meet the targets that a country such as Iran would want at this stage in its development, Batmanghelidj says the overall picture suggests that Iran will achieve growth this year and that it can do so for the foreseeable future under current circumstances. "This system has demonstrated that it can adjust to these external pressures," he says. "And even if there is another crisis, it will still be quite far off from collapse."