Declines and delays at gas fields threaten a key revenue stream but are also prompting talk of taking a different path, writes Kevin Morrison

The energy transition will throw up challenges for many resource-dependent emerging economies in the years ahead. For tiny East Timor, where prospects for development of the giant Sunrise natural gas discovery have been stalled for decades, the challenge could come sooner than expected.

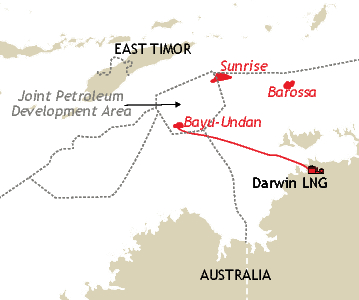

Within a few years, Dili stands to lose the revenue stream that it has relied on since gaining independence from Indonesia in 2002, as output dwindles at the Timor Sea's declining Bayu-Undan field, jointly administered by Australia and East Timor. Australian independent Santos in March approved the Barossa field offshore Australia's Northern Territory to supply backfill gas for its 3.7mn t/yr Darwin LNG plant in the state, replacing falling supplies from Bayu-Undan.

The field has provided gas for Darwin LNG since its first shipment in 2006, and received some respite in January when operator Santos said it would spend $235mn on infill drilling to extend the field's life by 12-24 months, with drilling to start in the coming months. Santos and Bayu-Undan partner Italian firm Eni this month also pledged to work on plans to use Bayu-Undan's facilities as a carbon capture and storage project, which if it goes ahead could provide a revenue fee for Dili.

Bayu-Undan, through taxes and royalties, has provided the bulk of the $23.1bn in oil income for East Timor's Petroleum Fund since it was created in 2006. A further $8.4bn has flowed into the fund from investment returns, and Dili has withdrawn about $12.5bn so far, leaving roughly $19bn in place at the end of last year, according to East Timor-based policy research organisation La'o Hamutuk researcher Charles Scheiner. The fund's remaining balance still dwarfs the size of the country's economy, which was around $1.9bn at the end of 2020, according to an estimate by Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

The flow of funds from Bayu-Undan has been declining in recent years at the same time as Dili has been increasing its withdrawal rate to underpin budget spending, including construction of a road and airport along its southern coastline as part of a plan to build an oil and gas infrastructure hub, Scheiner says. The hub, known as the Tasi Mane project, would include an oil refinery as well as a liquefaction plant and LNG export facility for the 5.1 trillion ft³ (145bn m³) Sunrise field, which faces mounting challenges to ever reaching development.

Sunrise sunset

Sunrise has faced problems ever since it was discovered in 1974, with Indonesia's occupation of East Timor in 1975-99 followed by a maritime boundary dispute with Canberra that put most of the field in Australian territory. Disputes over Sunrise have persisted even after the new maritime boundary was agreed in 2018, with Dili wanting to process the gas onshore but Sunrise operator Australian independent Woodside Petroleum preferring to do so through Darwin LNG.

Dili took a controlling share in the project by buying the stakes of Shell and US independent ConocoPhillips in 2018 for $650mn, borrowed from the Petroleum Fund. But this has done little to improve the viability of Sunrise for foreign investors concerned about political risk following Dili's part-nationalisation of the project, as well as the technical issues facing the field in the form of the 3.5km-deep Timor Trough between Sunrise and the East Timor's coastline.

Renewed international efforts to tackle climate change are already resulting in many potential LNG projects moving from possible to unlikely. And Dili says it is reconsidering buying the additional stakes in Sunrise and Tasi Mane, which would see a significant portion of the Petroleum Fund spent on a project with challenging economics. "East Timorwill have to move away from its dependence on oil and gas resources, and I am optimistic it can get through this challenge," Scheiner says.