Heatwaves and dwindling output from older fields have tightened the country's supply, write Antonio Peciccia, Auguste Breteau, Ellie Holbrook and Martin Senior

Egypt has been exporting increasingly less LNG during summer months as its supply surplus has shrunk, and has limited scope to reverse this in the short term.

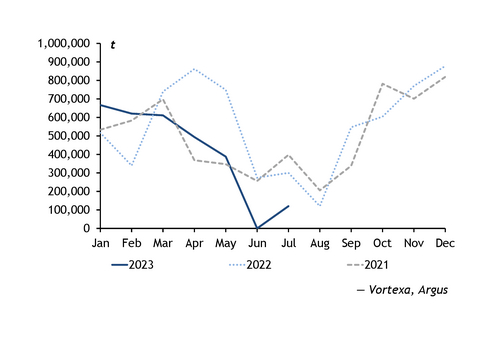

The country did not export a single cargo in June and loaded only two cargoes in July, one of which was delivered to its own 5.7mn t/yr Ain Sukhna import facility in the Red Sea, preliminary ship-tracking data from oil analytics firm Vortexa show. It has yet to load a single cargo in August and is not expected to do so over the remainder of this month, with the country's oil and mineral resources minister, Tarek El-Molla, last month saying exports will resume in October.

The minister points at high temperatures boosting cooling demand. In a country that generates about two-thirds of its electricity from gas-fired plants, a heatwave that swept the Mediterranean last month led the government to resort to power cuts in order to keep electricity demand at bay, as well as production cuts in some industrial sectors aimed at making more gas available for power generation. Urea producers received a letter from the government in mid-July requesting output reductions because of the summer demand for gas, with market participants telling Argus that production could fall by 30pc.

A seasonal slowdown in Egyptian LNG exports already has been observed in recent years and appears to have intensified (see graph).

The recurring summer tightness in the country's supply-demand balance is mainly the result of slowing output. After rising rapidly in the second half of the previous decade as several new gas reservoirs were brought to the market, upstream output appears to have peaked at 70.4bn m³ in 2021, before sliding to 67bn m³ a year later, data from the Joint Organisations Data Initiative (Jodi) show. Egypt produced 169mn m³/d in January-May, according to the most recent Jodi figures — which, if maintained throughout the rest of this year, would result in a further sharp drop to about 61.8bn m³ this year.

Some of the production decline may have been caused by dwindling output from older fields, which still account for a large portion of Egypt's output. But it may also stem from technical issues at the giant 849bn m³ Zohr field. A source at Egypt's Egas in February told Argus that output from Zohr would remain capped at 2.6bn ft³/d (26.78bn m³/yr) this year because of water infiltration issues. But Egypt's government last month denied any technical problems, saying Zohr is operating at its full production capacity, although adding that output from the field is averaging 2.3bn ft³/d. This is well below its peak capacity of 3.2bn ft³/d.

Slowing domestic output has been offset only partly by a gradual ramp-up in imports from Israel. These rose to 6.27bn m³ last year from 4.22bn m³ in 2021, and have already totalled 3.82bn m³ in the first five months of 2023. Israeli flows were expected to rise this year to reach the full contractual volume stated in the long-term deal between Egyptian consortium Dolphinus Holdings and partners in Israel's Leviathan field. But last year, Israel agreed to provide another 2.5bn-3bn m³ to Egypt through a pipeline running through Jordan, with Israel's energy ministry saying at the time that flows could climb further to 4bn m³/yr in the coming years.

Demand continues to rise

By contrast, domestic demand has continued to rise in recent years — except in 2020, during the first Covid-19 outbreak, and last year, when, with global gas prices dwarfing oil, Cairo approved measures aimed at rationalising electricity use and mandated a switch to fuel oil in power generation in a bid to shore up feedgas supply to LNG terminals.

Power-sector gas burn in Egypt last year fell to 34.7bn m³, from 37.9bn m³ in 2022 — the lowest since 2016. El-Molla admits that LNG exports were only possible last summer because the country was able "to replace the local consumption of gas by selling fuel oil or diesel". But non-power consumption continued to rise, jumping by 6pc last year, compared with 2021, when it had already almost entirely reversed the 10pc drop recorded during the first phase of the pandemic in 2020.

Egyptian pipeline exports to Jordan have also been increasing since they resumed in earnest in 2020, although they appear on course to drop this year — totalling 209.9mn m³ in January-May, down from 384mn m³ a year earlier.

A return to imports?

With no major gas production asset expected on stream in the coming years, reversing the trend in domestic output may depend on new discoveries that would take years to reach the market.

In the meantime, a further drop in domestic output may lead the country to curtail pipeline flows to Jordan during peak demand periods in the summer and potentially secure some occasional cargoes. But these would have to be delivered to Jordan's 3.8mn t/yr Aqaba LNG import terminal as the 170,000m³ BW Singapore floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU), which is still installed at Egypt's Ain Sukhna terminal, has been bought by Italian system operator Snam and is expected to move to its planned Ravenna terminal next year. Last month, Aqaba received its first LNG cargo since June 2022, before which time the terminal was idle since October 2020, when a 1.1mn t/yr LNG supply deal between the country's state-owned Nepco and Shell expired.

In June, Egas signed an agreement with Nepco aimed at allowing the firm to use the 160,000m³ Golar Eskimo FSRU stationed at Aqaba until the ship's charter expires at the end of 2025 — a similar arrangement to the one that allowed Egypt to import LNG through Jordan in the previous decade. Under a separate deal with Jordanian-Egyptian firm Fajr, Egas also pledged to supply LNG to Jordan in order to meet the needs of the country's industrial sector. But part of the LNG supplied would be "repumped when needed to the Arab Republic of Egypt through pipelines extending between the two countries", Jordanian minister of energy and mineral resources Saleh al-Kharabsheh said at the time of the deal.