Trump's threats are unlikely to slow the ambitions of the region's rising oil champions, writes Carla Bass

Dwindling crude producers Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia have been the first to draw US president Donald Trump's attention early in his second term, mostly over drugs and migration. But it is other Latin American producers — namely Brazil, Guyana, Argentina and Suriname — where rising crude output may garner more focus by the end of his time in office.

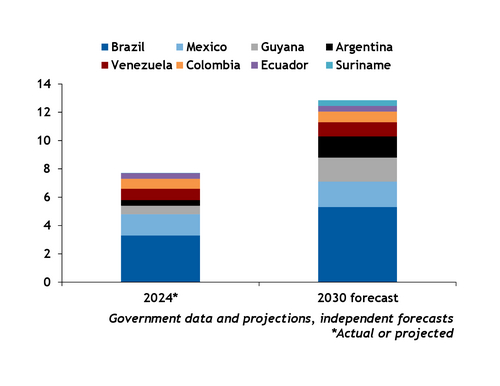

Those four South American nations could push the Latin American region as a whole to near current US crude output of roughly 12mn b/d by 2030, up from 9mn b/d in 2024. US output is likely to remain in front, but at a slower rate of growth, with some forecasts pointing to a plateau at about 14mn b/d by 2030. Trump's migration-fuelled tariff tiff with Colombia last weekend highlighted the type of regional disagreements that could trip up such a drive. But other issues in 2025 will be critical as well.

Brazil could add the biggest share to 2030, at 2mn b/d, taking projected output to 4.6mn b/d from 3.3mn b/d in November. State-controlled Petrobras and the administration of President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva have shown a will and a way. But Brazil will need to reconcile its climate and crude output ambitions, specifically whether it will drill in the environmentally sensitive equatorial margin region.

Neighbouring Guyana could add almost 1mn b/d to reach 1.7mn b/d by 2030, as output has already grown exponentially since ExxonMobil brought on line the prodigious Stabroek field. Delays could occur as the country faces a presidential election in October for the first time since it became a sizeable crude producer, and discontent over contract terms could emerge.

Brazil's neighbour Argentina could add at least 600,000 b/d to its Vaca Muerta output to reach up to 1.5mn b/d by 2030 as it finally taps its massive deposits. It hit record output of 717,000 b/d in 2024. President Javier Milei's frantic bureaucracy busting would need to continue, focusing on financial restrictions that have limited investment. Logistical and workforce hurdles remain in the remote region.

Finally, Suriname could become a crude exporter if it moves toward reaching a forecast 400,000 b/d of output by 2030 from minimal production now. The changes mostly rely on the success of new production from its offshore, with TotalEnergies' $10.5bn GranMorgu oil project the first due to start. Shell has also restarted its offshore exploration there.

Sitting it out

The gains will offset mostly flat or declining output expected for Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela, which together still contribute about 3.5mn-4mn b/d. Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum, in office until 2030, wants to cap output at 1.8mn b/d, even as state-owned Pemex has struggled when trying to produce more. Trump's threat to impose a 25pc tariff on Mexico's exports could dampen even that ambition, and Sheinbaum is also continuing a push — so far with limited results — to export less crude and refine more of it domestically.

Colombia's president Gustavo Petro has vowed to wean off hydrocarbons production, but he faces an election in 2026 amid waning popularity, possibly providing an opening for a different policy. Venezuela's fate and future crude output relies on US crude sanctions and whether President Nicolas Maduro clings to power. Maduro is aiming for 1.5mn b/d from near 1mn b/d now, but the waivers that have allowed this may depend on his willingness to receive US deportees.

Finally, the newer South American supply may fully come on stream just as some forecasts indicate oil demand will begin to wane, possibly capping growth. Still, the balance of power in the Americas crude markets looks likely to shift a little farther south.