Without tangible climate finance backed by bigger ambitions post-2025, progress on emissions cutting looks unlikely, write Georgia Gratton and Caroline Varin

Climate finance has become both the overriding topic and the stumbling block at a raft of recent climate summits, and it looks likely to dominate discussions at the UN Cop 28 conference later this year. A lack of climate finance from developed countries barred progress on mitigation — cutting global emissions — both at Cop 27 last year and at UN talks in Bonn in June.

Climate finance is a broad umbrella term that encompasses money for mitigation, loss and damage — the unavoidable and irreversible effects of climate change — and adaptation — adjustments to avoid these impacts where possible.

A key focus for developing countries is a $100bn/yr climate finance goal, which wealthy nations agreed to provide by 2020 but have still not reached. Cop 28 presidentSultan al-Jaber has called on donors to "close out the pledge", and the US, Germany, Canada and France are confident that developed countries will reach the target this year. But it only runs through to 2025, meaning that discussions are needed for financial commitments beyond 2025. Parties to the UNFCCC — the UN's climate body — agree that, for trust to be restored, lessons must be learned from the missed goal and finance access issues, but agreeing on a new number will be difficult.

The missed 2020 goal "came at some cost of trust between developing countries and developed nations", Colombian government climate finance adviser Sofia Vargas Lozado says, adding that removing access barriers to this finance is a crucial issue. And the current commitment is only a fraction of what developing countries need, parties and observers warn. "It is not only about volume," Vargas Lozado says. Qualitative elements must be built into the next commitment, including not adding to the debt burden and providing financing that works for developing countries' needs, she says, proposing a larger share of concessional finance and more predictability.

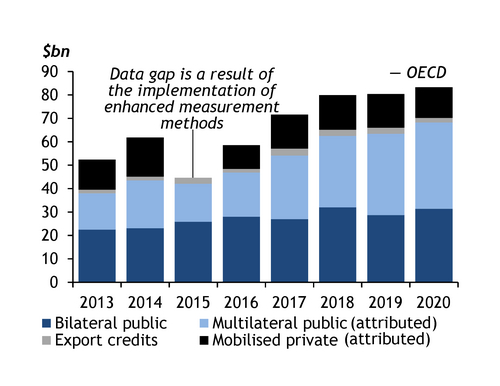

Loans accounted for 71pc of international public finance in 2020, or $48.6bn, which included concessional and non-concessional loans. In comparison, grants held a 26pc share, OECD data show. Most agree that more needs to be done to deal with the burden of debt on developing countries — which often suffer most from the effects of climate change — but the amount of finance required for the new goal, where the money will come from and what it will cover remain huge sticking points. "To open the way for agreement, this year's deliberations must start translating needs into quantitative estimates, agreeing on an initial order of magnitude — or at least discuss the options for agreeing on a quantitative figure," think-tank IISD says.

From billions to trillions

Developing countries, such as India and Zambia, want the so-called new collective quantified goal (NCQG) on climate finance to be based on the costs outlined in a UNFCCC report published last year. The needs identified are broadly similar to those recognised in a G20 declaration this month, which says that $5.8 trillion-5.9 trillion is required before 2030 for developing countries to implement their climate plans.

Developed countries agree that the figure needed will be in the range of trillions. "The Cop 21 decision on the NCQG states that the needs and priorities of developing countries should be taken into account when setting the new goal," Norway said in June. But the EU and Norway stress that "taken into account" does not mean that all needs must be reflected in the goal. "It is economically unrealistic to expect the new goal to cover all needs and priorities, considering the evolving and highly diverse nature of the needs of developing countries," the EU says. And "countries with high emissions and higher economic capacities, including those that under the Paris agreement define themselves as developing country parties, should be part of the contributor base," Norway adds, reflecting tensions similar to those recorded in discussions on the establishment of a loss and damage fund. The EU says the new amount needs to reflect "changed economic realities".

During loss and damage negotiations last year, the EU and other countries noted that talks revolved around a list of developed economies dating from when the UNFCCC was set up in 1992. But some countries' economic circumstances — namely China — have changed significantly since then.

Public and private

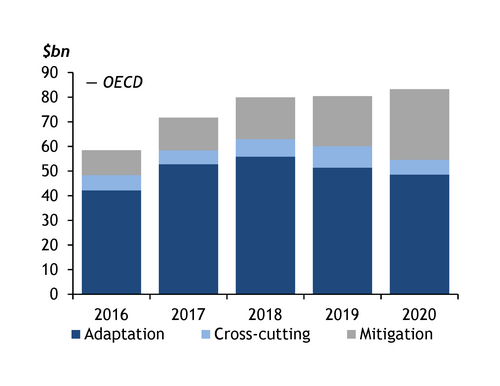

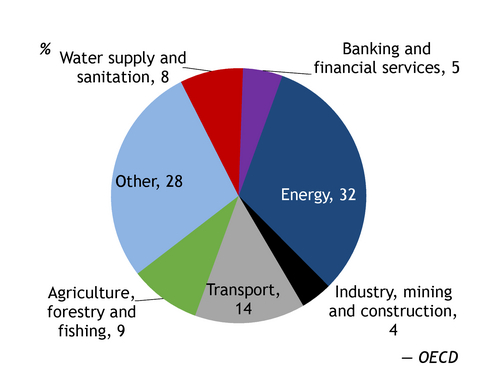

UNFCCC executive secretary Simon Stiell wants to see more clarity on how the new goal will be divided between mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage. Public funding from developed countries largely focuses on mitigation, although adaptation is gaining ground. Developed countries are on the right trajectory to reach their commitment to double adaptation funding by 2025, relative to 2019 levels, according to think-tank ODI. But observers warn that adaptation and loss and damage do not attract private-sector money.

EU member states "recognise their responsibility in providing assistance to the most vulnerable developing countries as a core layer of the new goal". But global mobilisation of climate finance requires multiple sources, instruments and contributions from public and private actors, both international and domestic, according to their respective responsibilities and capabilities, the EU says.

But "unless public investment takes a strong lead, I don't think the private sector can solve this problem", the UN trade and development body's director of globalisation and development strategies, Richard Kozul-Wright, says. For Kozul-Wright, the reform of global financial architecture has a key role to play. This echoes Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley's Bridgetown Initiative — a practical path to revamping the global financial system, focused on poverty and climate change — which gained some ground at a Paris summit in June.

That event saw concrete steps taken by governments and multilateral development banks (MDBs), taking cues from the Bridgetown Initiative. Countries, non-governmental organisations and others have long called for MDB reform, arguing that they could do more to muster and distribute climate finance. The G20 this month noted the "enhanced role of MDBs in mobilising climate finance".

The World Bank and European Investment Bank set out the option for countries faced with climate-related natural disasters to pause debt repayments, while the UK made a similar pledge. These were incremental steps but, if built on, they may go some way to restoring developing countries' trust and set the stage for agreement on further action at Cop 28.

"Progress overall could be blocked if developed countries do not make concrete pledges for scaling up climate finance overall — for mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage," non-profit Centre for International Environmental Law senior campaigner Lien Vandamme tells Argus. "Countries that bear the most responsibility for the climate crisis have failed to meet their obligations to provide finance to those who have done the least to contribute to the problem and face the greatest impacts. These broken promises have undermined trust and, ultimately, progress," Vandamme says.

Without tangible climate finance and an ambitious new goal for post-2025, progress on reducing emissions is very unlikely. And the bigger the increase in temperature, the more frequently catastrophic loss and damage events will occur — pushing the bill higher still.