The government must provide clarity soon as some companies are holding back investment until regulations are in place, writes Lucas Parolin

The Brazilian government's Gas do Povo programme will significantly boost LPG demand in the country if it is introduced as planned in November. But the domestic market is still waiting for clarity on proposed regulatory changes, which some suggest could promote illegal practices and impede investment, delegates heard during Liquid Gas Week in Rio de Janeiro over 22-26 September.

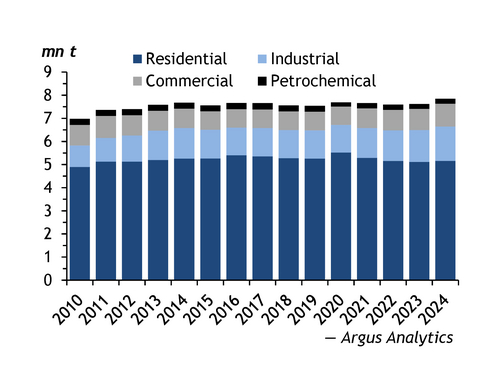

Gas do Povo — which translates to "people's gas" and is also known as Gas for All — is a subsidy scheme that was launched last month and will provide free LPG to low-income families in off-grid areas of Brazil. It will supersede the outgoing Auxilio Gas programme, targeting a further 15.5mn homes, bringing the total number of beneficiaries to about 21mn. The goal is to reduce these families' reliance on wood and charcoal for cooking. The scheme will start in November, with capacity expected to be reached in March.

The programme alone will increase LPG sales by 5-8pc, Brazilian LPG association Sindigas president Sergio Bandeira de Mellosaid on the sidelines of the event. But a new proposal by hydrocarbons regulator ANP to allow the refilling of 13kg gas cylinders remotely and in small increments may hinder investments and open the gates for organised crime, market participants said. The plan is to enable customers to take a cylinder to a refilling site and only buy a desired amount of LPG rather than a complete refill or a replacement cylinder from a retail outlet. This will help to lower LPG prices and allow lower-income families to purchase smaller volumes at a cost more in line with their household budget, according to ANP.

But market participants see flaws in the plan. "If anybody can use anybody's cylinder, you run the risk of bringing organised crime to the distribution chain," de Mello said. The change would also permit new participants to enter the market without investing in new cylinders, he added. Allowing the purchase of fractional amounts of LPG additionally introduces higher costs for market participants, Carlos Ragazzo, a law professor at think-tank Fundacao Getulio Vargas, said. This incentivises participants to seek ways to reduce costs. "There's a huge incentive… to not act correctly," he said, such as circumventing safety rules or avoiding taxes.

The resale of LPG cylinders at premiums to official retail rates in areas dominated by criminal gangs is one of the main sources of income for Brazilian drug traffickers, ANP supply monitoring superintendent Ary Sergio told delegates. ANP is focused on ways to identify how the cylinders have ended up in the hands of criminal groups, he added.

Regulation time

ANP's main focus right now is regulation under Gas do Povo, director Artur Watt said. The agency is still waiting to receive information from the mines and energy ministry but the regulation can still emerge "in a timely manner", he said. But decisions need to be made now, according to de Mello, because companies are "indisputably" holding back investment in cylinders until the regulations are in place. "March is the deadline for the programme to be fully operational," he said. "So, ideally, for private companies, this [regulation] will be fully approved and the law sanctioned before [legislative] recess." Brazil's legislative branch begins its recess in December, with activities returning in February.

Brazilian distributor Ultragaz is waiting for the regulations to be put in place and is hoping that the process is resolved quickly, chief executive Tabajara Bertelli Costa said. But the government may still choose to oppose ANP's proposals. Brasilia always seeks to ensure that policies "provide stability to investments", mines and energy minister Alexandre Silveira said, while calling for "common sense, so that we always have legal stability to attract investments for LPG".