In the war of words over decarbonisation, aviation gets a lot of stick. Planes gulp jet fuel, they belch exhaust, they make a lot of noise, and people see them flying overhead from dawn till midnight.

To make matters worse, unlike in shipping, or in road transport – which together actually account for almost 90pc of all transport emissions – aviation currently has no alternatives to hydrocarbon fuels.

Global aircraft passenger numbers are expected to double by 2050, so CO2 emissions will carry on rising in both absolute and percentage terms unless action is taken.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), currently produced from vegetable oils, waste oils and residues, is the only substance that can cut aviation emissions without a decade-long redesign of aircraft engines and infrastructure. Yet the growth of SAF is caught in a three-way standoff between producers, airlines, and governments.

Analysts expect a global oversupply of SAF until 2030, when EU mandates brought in this year get much sterner. And ironically, even though Argus SAF prices in northwest Europe hit a fresh 2-year high in November, major players like BP and Shell are delaying or cancelling SAF projects. Temporary factors—plant maintenance and weak imports—tightened supply this year, pushing prices to over $2,900/tonne, almost four times the cost of conventional jet, but relief is expected.

Such market swings can undermine the investment climate. Price jumps are the product of a relatively illiquid market shaped by regulation, and even though commodity cycles are normal, volatility in this developing market is destabilising, and can erode confidence among both investors and policymakers.

In the face of climate urgency, industry-wide underinvestment risks missing an opportunity to build long-term capacity.

Meanwhile suppliers of conventional jet face billions of dollars in penalties unless they meet government SAF and e-SAF quotas. Airlines are on the hook too – they must stump up for SAF-blended jet fuel or face penalties for refuelling away from major EU airports.

Governments rightly recognise that bio-SAF alone cannot decarbonise aviation, because renewable feedstocks, mostly used cooking oil, are a finite resource. There are not enough McDonald’s on the planet to feed 30,000 planes every day.

As a result, the industry is banking on fully synthetic e-fuels – molecules assembled from scratch out of hydrogen atoms and carbon dioxide. Mandates for hydrogen-derived e-SAF kick in from 2028 in the UK and from 2030 in the EU. Yet the industry is nowhere near ready. Meeting the quotas will require around 600,000 tonnes annually—roughly 12 commercial-scale projects based on 50,000t/yr median project size tracked by Argus. Of the 70 proposed e-SAF plants in the UK and Europe tracked by Argus, no commercial scale plant has yet reached final investment decision (FID). Plants take 3–4 years to build, so FIDs must be taken within the next year to have any chance of Europe meeting 2030 targets.

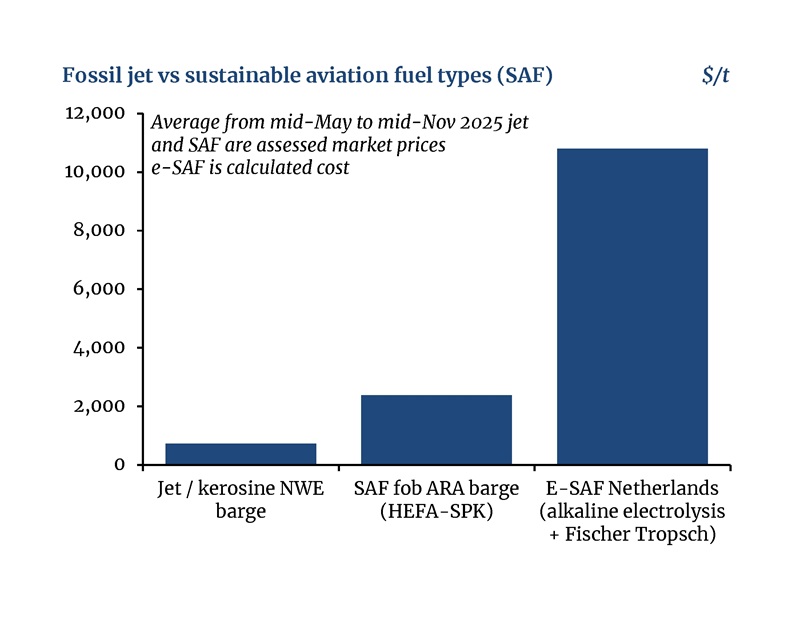

E-SAF as a pioneering technology is more expensive than bio-SAF and conventional jet fuel. The new Argus calculated costs for e-SAF production in November 2025 show it currently costs 13 times the assessed market price of conventional jet fuel and 3.5 times the price of bio-SAF (produced via the HEFA SPK pathway) in northwest Europe.

For as long fossil jet fuel prices fail to reflect its environmental cost, the structural price gap to cleaner alternatives will remain, requiring long-term policy support to bridge.

Long-term offtake agreements are essential for financing, but airlines – accustomed to short-term contracts and tight margins – are reluctant to commit tens of millions of dollars to advance purchases of a product whose price may fall as technology matures. This disconnect between supply obligations and demand is stalling investment.

If no e-SAF is supplied in 2030, penalties for EU fuel suppliers could total around $10bn. Moreover, the obligation doesn’t disappear but rolls forward each year. There is debate whether the EU would enforce such penalties, or back down. Such doubts further contribute to investment hesitation. And the UK and EU’s work on subsidy mechanisms is painfully slow.

Cost remains a major hurdle. While some savings may come from scaling and design optimisation, the bulk of e-SAF cost is the cost of clean electricity – renewable or nuclear. This price is unlikely to fall significantly.

This is not to dismiss SAF progress. The EU, UK, and several US states deserve credit for their leadership; and countries like China, Singapore, South Korea, and Indonesia are preparing mandates. Momentum is real. But addressing today’s bottlenecks is essential to avoid real shortages tomorrow.

Critics, including some aviation CEOs, have called SAF a “nonsense.” Others argue climate funding should prioritise cheaper CO₂ abatement, like renewables and electric vehicles. But every sector must clean up its own emissions, and aviation won’t be spared. Delaying action only defers the inevitable and increases future costs.

SAF adoption is growing faster than many realise. Millions of passengers flew on SAF-blended fuel this year. But the sector faces mounting challenges. Without urgent remedies, Europe risks sleepwalking into SAF failure just as the need for climate action becomes more pressing.

Author name: Aidan Lea, Head of European SAF pricing, Argus

Argus drives transparency into the growing sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) market with industry leading price indexes for biogenic SAF such as Argus HEFA-SPK SAF fob ARA range.

We are now pleased to announce the launch of new modelled production cost indexes for e-SAF, which are used to support decisions around project investment and offtake agreements.