Indonesia's implementation of a 50pc biodiesel (B50) blend mandate and ongoing palm plantation seizures may raise palm oil prices and reduce global waste oil supply, likely keeping palm oil mill effluent (Pome) oil prices supported in 2026.

The country raised its biodiesel blend target by 5pc to 40pc starting from February 2025 and is targeting another 10pc increase to 50pc by the second half of 2026.

The higher blending mandate would lower total palm oil exports by about 11-12pc in 2026 compared with 2024 and 2025, Indonesian agriculture ministry official Baginda Siagan said at the 21st Indonesian palm oil conference (IPOC2025) in November. This would likely support an increase in crude palm oil (CPO) prices, industry analysts said.

Prices of CPO and palm-based waste oil like Pome oil are linked because market participants historically priced Pome oil at a set discount to CPO values, and they are both feedstocks for biofuel production. But waste oil export values have mostly been at a premium to CPO this year due to Indonesia's move to suspend exports of unprocessed Pome oil and used cooking oil (UCO) since 8 January, tightening the global supply of waste oils.

Indonesia has yet to resume issuing export permits. The restrictions have since driven exporters to explore refining Pome oil for exports. Refined Pome oil exports totalled 440,000t in January-November, according to Kpler data. No refined Pome oil was shipped in 2024 prior to the export pause because exporters directly shipped unrefined material. Refined Pome oil has lower metals and impurities than unprocessed material and can be used for hydrotreating to produce hydrotreated vegetable oil or hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids synthetic paraffinic kerosene (HEFA-SPK) with less processing than crude Pome oil. Argus launched the refined Pome oil fob Indonesia assessment on 15 October to reflect the value in this emerging export market, and it has since been priced above rival regional biofuels feedstock assessments.

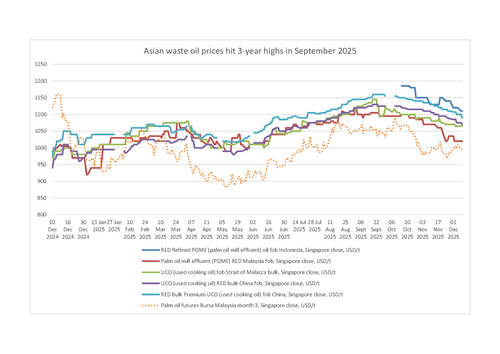

Indonesia's export pause was a key factor driving up waste oil prices in the region to three-year highs in September (see chart).

The duration of Indonesia's ban on crude Pome oil and UCO exports remains uncertain, but the government may be tempted to maintain restrictions to keep more feedstocks available to expand domestic biofuels production. This would continue to limit seaborne supply and support prices on a fob basis.

Speaking at IPOC2025, Indonesia's palm plantation fund (BPDP) head suggested exploring alternative waste feedstocks such as UCO for use in the B50 programme to reduce Indonesia's reliance on CPO as biodiesel feedstock.

State-owned Pertamina is already trialling sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) production through co-processing UCO at its Cilacap refinery since the second quarter of 2025, and shipped about 32,000 litres of UCO-based HEFA-SPK in its first shipment in August. The country is targeting the production of 1mn kilolitres/yr SAF by 2030.

Plantation seizures may squeeze CPO output

Palm oil production in Indonesia may be squeezed by the government's ongoing efforts to reclaim plantation lands it said were illegally acquired this year.

The Indonesian government in January formed a forestry task force for this purpose and reclaimed over 3.3mn hectares of plantation land by August, according to its website. The land will be transferred to and managed by state-owned Agrinas Palma Nusantara, which was set up in February to oversee the confiscated land. Agrinas has been recruiting staff to operate its plantation business but the availability of harvesters still poses a challenge, it said in a press release on 1 December.

Many in the sector expect the change in land management to reduce plantation efficiency starting in 2026. But the extent of yield and production losses caused by the land seizures remains uncertain, said industry analyst Thomas Mielke at IPOC2025. He estimated palm oil output in the country may decline to 49mn t in 2026 from 49.4mn t in 2025.

Ministry officials at IPOC2025 did not comment on the ongoing palm plantation seizures.

The collection and export of Pome oil from mills may also fall on the back of fewer fresh fruit bunches harvested from oil palm plantations due to the land seizures. Less CPO available for processing into palm olein for domestic cooking oil could also cause UCO supply to shrink.

Traceability concerns continue to threaten demand

Meanwhile, concerns surrounding Pome oil traceability have continued among European buyers this year, prompting some EU Member States including Portugal, Germany and Ireland to disincentivise Pome oil usage in their biofuels mandates. Most recently in October, the Dutch emissions authority (NEa) said that it will investigate the international Pome oil supply chain with a focus on "fraud risk", and that any findings could be used in policy recommendations.

European Pome oil demand is currently expected to remain stable in the near-term at around 1.9mn t/yr, according to Argus Analytics, but removal of policy support by more markets in the new year could tip the balance. Higher demand for Annex IX Part A feedstocks under the RED III may drive other EU countries to absorb Pome oil volumes diverted from markets that have chosen to disincentivise the feedstock by removing it from the classification.