Proposals to expand the BRICS grouping have reignited speculation over de-dollarization of the world economy, but rumours of the dollar’s imminent demise seem premature. Atlantic Basin economies are learning to live with higher-for-longer interest rates, leaving sub-par Chinese recovery as arguably the greatest short term risk for oil and commodity demand.

Last week saw key leadership gatherings for BRICS nations and Central Banks. Original BRICS members Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa convened in Johannesburg, highlighting plans for expanding trade using local currencies and continued exploitation of energy sources including fossil fuels.

Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were invited to become full members of BRICS from 1 January 2024. The enlarged group represents 46% of the global population, 37% of world GDP in PPP terms and 40-50% of global reserves of oil, gas, coal and graphite, 47% of solar PV capacity and 74% of world rare earths reserves. Leaving aside ongoing political tensions between members, the activation of this larger grouping could potentially hasten the de-dollarisation of world commodity trade. Despite the recent rise in US dollar import costs, interest rate pressures on high-debt developing economies and Washington’s imposition of sanctions on dollar trade with Russia, nonetheless the size, openness and transparent regulatory regime of the US economy, plus its persistent net deficit, continue to encourage the holding of dollars. In short, despite the BRICS’ best efforts at diversification, rumours of the dollar’s imminent demise may be premature.

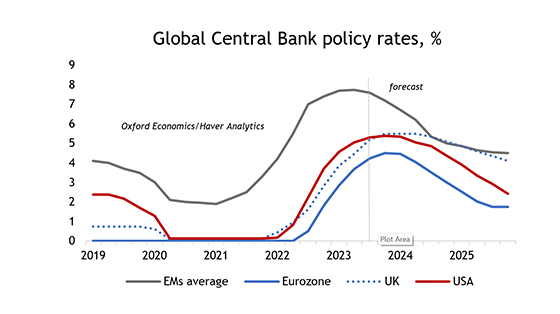

While BRICS expansion may have long-term implications for the dollar’s role as the most widely used international medium of exchange, the actions of the world’s central bankers arguably have greater relevance for oil and commodity markets short-term. Advanced economy interest rates since early-2022 have been hiked at a speed not seen since the early-1980s. The aim is to quell post-pandemic inflationary pressures which themselves were exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. The US Federal Reserve has led the way, so Fed. Chair Powell’s comments last Friday In Jackson Hole were keenly awaited for signals on whether the current 5.5% rate represents a ceiling before loosening begins.

Powell noted that in the absence of above-trend GDP growth or a reversal of recent labour market cooling in the months ahead, the US may indeed have seen peak interest rates. But equally he cited a determination to further reduce inflation, noting that the Federal Reserve’s target remains 2%. Categorising the three key elements of US inflation as goods, housing and services excluding housing, Powell noted that further labour market loosening is required before the services component is tamed. He concluded by saying that rates will remain in restrictive territory until inflation moves sustainably towards the 2% target, implying interest rates are unlikely to fall until well into 2024.

China faces different challenges. Official manufacturing PMI data this week show a fifth month of contraction. The real estate sector continues to shrink and May-to-July highway traffic remains -57% below 2019 levels. Despite clear evidence of slowing post-pandemic economic momentum, the People’s Bank of China confined recent policy loosening to a 10bp cut to 3.45% in the one-year loan prime rate (LPR), unexpectedly leaving the five-year LPR (the mortgage reference rate) unchanged at 4.2%. In addition to concerns over bank profitability, Beijing has an eye on a weaker Yuan, the risk of capital flight and overall debt levels that now rival those of the US as a share of GDP. It appears that fiscal, not monetary, policy may be the tool of choice to reinvigorate Chinese recovery.

Sustained 5.5% interest rates in the US will ultimately curb employment, consumer spending and activity levels, implying a sharp slowdown in both GDP and oil demand growth by year-end. But with the Advanced Economies now minor contributors to global oil demand growth, the real downside risks for the oil market lie in Asia. For now we assume that China attains its 5% GDP growth target for 2023, leading to growth of around 900 kb/d in apparent oil demand, 47% of total global growth this year. In the absence of more aggressive stimulus measures though, that level of growth may be a stretch.

Author David Fyfe, Argus Chief Economist