Latin American national oil companies (NOCs) are shifting their business models to be in line with climate ambitions not only by investing in clean energy technologies but also by optimizing their oil assets.

"Companies are closing [drilling] projects in places where they think the carbon intensity is too high," said Luisa Palacios, senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University and former chairwoman of the board of directors at US-based refiner Citgo. "They are optimizing their portfolios," she added in an event in New York City.

Major Latin American economies strongly depend on exporting a large share of their fossil fuels production, such as oil and coal, given the region's vast resources. But because of stronger public and political support to set targets to limit the increase in the average global temperature to 1.5°C by 2030, the location of those exploration projects is getting more important. "Where your resources are is going to impact the political economy of developing resources," Palacios said.

Earlier this year, the Ecuadorean government left the decision to stop oil activities in the Yasuni natural reserve in the Amazon to its citizens through a referendum. Over 59pc of voters chose to stop oil production within a year.

In the case of Chile, it is much harder to produce any kind of energy or mining project in the wooded Patagonia region, than in the Atacama Desert, said former Chilean energy minister Juan Carlos Jobet.

State-controlled Petrobras' plans to drill an exploration well near the mouth of the Amazon River in Brazil has created some tensions within President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva's coalition government. His environmental supporters see the plans as calling into question the credibility of Lula's vows on the international stage to protect the environment, although the environment ministry has so far help up the drilling.

The Brazilian president's climate advocacy contrasts with his defense of the country's fossil-fuels industry. Most recently, finance minister Fernando Haddad said that Petrobras is likely to drill the exploration well despite the lack of a permit so far.

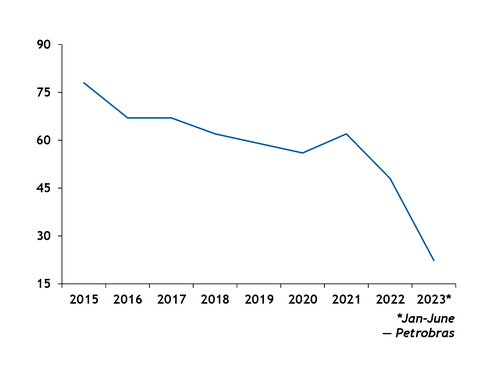

Petrobras' strategy to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions is largely focused on the production of pre-salt crude, which is known for its lower carbon intensity compared with other types. The firm is also the only Latin American NOC that uses carbon capture, utilization and storage in its operations.

Fossil-fuels phase out calls

Meanwhile, Chilean president Gabriel Boric and his Colombian counterpart Gustavo Petro called for an end to the consumption of fossil fuels to achieve 2030 and 2050 climate goals.

"The fossil-fuel crisis gets solved by halting the burning of fossil fuels," said Boric at the UN's Climate Ambition Summit in New York City, even though there are many state-supported oil companies throughout the region.

Petro pointed out that demand for fossil fuels must decline first so his country can transform its economy away from oil and coal. "Our country needs to stop exporting oil and coal, but [global] consumption needs to decline every year," he said. "What would happen if Colombia or Venezuela stopped their [oil] exports? Nobody would be sitting with us right now."

More financial support was also one of the main points highlighted by the South American leaders. Boric called for including the private financial sector in climate debates and for a equitable distribution of funds to cover the costs produced by climate change in vulnerable regions.

The two presidents also called for more solidarity towards the most hurt by climate change. Petro called for increasing the $100bn/yr in climate finance promised by developed countries to developing countries in 2009.

He also called for a reform of the multilateral finance system, pointing out that the greatest efforts to finance the decarbonization of economies will come from the public sector.