The question of whether the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is in the crosshairs of US President Donald Trump's deregulatory agenda is weighing on the market as his administration begins to challenge state climate policies in court.

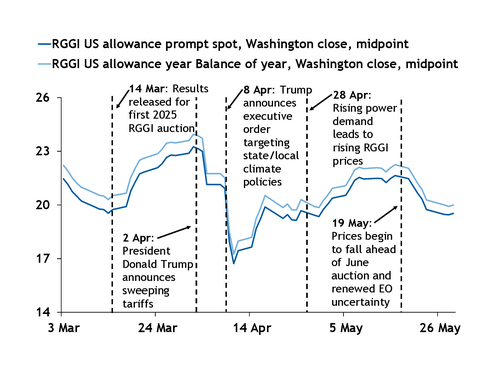

Ever since Trump issued an executive order on 8 April directing the Department of Justice (DOJ) to identify and potentially challenge a slate of policies states have enacted to address climate change, the power plant CO2 emissions market has been in a state of volatility. Market participants are unsure whether RGGI, a collective of 10 northeastern US states, could be targeted by the federal government.

The market plunged immediately after Trump issued the order, and even now, its potential legal effects continue to weigh on the market, despite the presence of more bullish factors, such as expectations for heightened summer electricity demand.

US attorney general Pam Bondi is expected to release a report sometime in early June which could provide more clarity on the state programs that may be targeted by the administration or Congress — and whether RGGI is on the federal government's radar.

The DOJ has already filed lawsuits against four states, including New York and Vermont, for their attempts to hold fossil fuel companies responsible for the climate change-related harms resulting from their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In addition, Maine conservatives have asked Bondi to review the state's policies, including its membership in RGGI.

Litigate now, ask questions later

While Trump's executive order has cast a shadow of legal uncertainty over RGGI and other environmental markets, the order itself does not have much of a direct legal effect.

Rather than directing federal agencies to issue regulations — which are, by law, subject to notice and comment periods — the order only requires the DOJ to investigate state laws and policies that could negatively affect US energy production.

The lack of such lengthy administrative procedures could make the order "highly vulnerable to being overturned by the courts" and is an example of how much more "reckless" the Trump administration is now compared to the first term, said Michael Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University.

During Trump's first term, many states leveraged existing laws and regulations to prevent federal projects from going through, and those lessons are informing how the administration is now addressing what it perceives as state overreach, according to Matthew Dobbins, a partner at Vinson & Elkins specializing in environmental issues.

The Trump administration does "not want state laws being abused to defeat things that have national implications like energy," he said.

In addition, the order is likely meant to delay or even stop states from implementation of more-ambitious climate policies already under consideration.

"Certainly, the net legal effect is … intended to chill state leadership on climate action, which has been a big part of the United States' climate response in the last decade or more," said Joshua Rosen, an associate at Foley Hoag in Boston practicing energy and climate law.

While the lawsuits that the Trump administration has or intends to initiate will likely take many years to resolve, they are reflective of a "flood-the-zone" or "flood-the-field" strategy, both Dobbins and Rosen said. Even if those challenges are unlikely to succeed, they could still temporarily halt policy implementation, something that could significantly affect cap-and-trade markets such as RGGI, Dobbins said.

Out of sight, out of mind

While Trump's order broadly directs Bondi to identify laws that address climate change, GHG emissions, and collect carbon "penalties" or "taxes", it remains to be seen whether RGGI is in the sights of the administration.

Unlike California, whose cap-and-trade program was explicitly called out in the order, there has not yet been any mention of RGGI.

Even if there are more compelling legal arguments against RGGI, the administration might prioritize going after California's program for political reasons, as it is a much more well-known market in a state that has historically been at odds with Trump, according to Dobbins.

"I think if they can take down or get any traction attacking the California cap and trade program, then RGGI is going to be next in the crosshairs," he said.

In addition, RGGI has been running for nearly 20 years and, in that period, the program has faced a number of unsuccessful lawsuits, Gerrard said.

But Rosen noted that "the success of the RGGI program could make it in the crosshairs" of the Trump administration's effort to draw attention to its deregulatory agenda when it comes to climate policy and "have sort of a soft effect of intimidating states."

The administration could challenge RGGI based on the Compact Clause of the US Constitution, which forbids states from entering into agreements without approval from the US Congress.

But while interpretations of that clause have been more nuanced in the past, there could be a legitimate argument to be made, particularly if a case reaches the US Supreme Court, which, under its current makeup, has been more "textually focused," said Dobbins.

The dormant commerce clause, a constitutional legal doctrine barring states from discriminating against out-of-state businesses or burdening interstate economic activity, could be another avenue for the federal government. Essentially, the doctrine could be used to argue that RGGI puts an undue economic burden on electricity generators in member states compared to out-of-state generators that import electricity but do not have to buy allowances for compliance.

The federal government could also claim that RGGI is undermining its regulatory authority granted by the Clean Air Act — an argument that has already been used in its lawsuits against the New York and Vermont climate "superfund" laws.

But that argument might be moot since the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has plans to repeal a slew of environmental polices, Dobbins said.

In addition, the Clean Air Act is designed in such a way that "federal standards are a floor, not a ceiling, and states may set stronger standards," Gerrard said.

There is also the question of how the RGGI states might respond collectively to a lawsuit from the federal government. Many states are facing pressure from high energy costs, causing even liberal lawmakers to balk at enacting more ambitious policies. This could result in a more "fragmented" response from RGGI states, particularly as the 2026 elections draw closer, Dobbins said.

Still, while affordability concerns are a major pressure point for politicians, RGGI has been successful in not only lowering CO2 emissions, but also providing funds for energy efficiency programs — a somewhat non-partisan climate issue, according to Rosen.

RGGI allowance prices have been rising since last year due in large part to expectations of rising electricity demand from the buildout of power-hungry data centers. The program has been in a review process that includes plans to extend the emissions cap beyond 2030.

But that review, which started in February 2021, has been subject to multiple delays and is currently slated to complete sometime this year. It remains to be seen how Trump's executive order could affect the progress of the review.

RGGI has not yet responded to requests for comment.